|

Southern African

topography and erosion history:

plumes or plate tectonics? |

Andy Moore1,2, Tom Blenkinsop3 & Fenton

(Woody) Cotterill4

1African Queen Mines Ltd., Box 66, Maun Botswana.

2Dept

of Geology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa, andy.moore@info.bw

3School

of Earth and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University,

Townsville, QLD4811, Australia, thomas.blenkinsop@jcu.edu.au

4AEON

- Africa Earth Observatory Network, and Department

of Geological Sciences, and Department of Molecular

and Cell Biology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch

7701, South Africa, fcotterill@gmail.com

This webpage is a summary of: Moore,

A., Blenkinsop, T. & Cotterill, F. Southern African

topography and erosion history: plumes or plate tectonics?,

Terra Nova, 21, 310-315,

2009.

ABSTRACT

The physiography of southern Africa

comprises a narrow coastal plain, separated from an

inland plateau by a horseshoe-shaped escarpment. The

interior of the inland plateau is a sedimentary basin.

The drainage network of southern Africa is characterized

by three river divides, broadly parallel to the coastline.

These features contrast strongly with the broad dome

and radial drainage patterns predicted by models which

ascribe the physiography of southern Africa to uplift

over a deep mantle plume. The drainage divides are

interpreted as axes of epeirogenic uplift. The

ages of these axes, which young from the margin to

the interior, correlate closely with major reorganizations

of spreading regimes in the oceanic ridges surrounding

southern Africa, suggesting an origin from stresses

related to plate motion. Successive uplifts

of southern Africa were focused along respective

epeirogenic axes, forming the major river divides.

These events initiated cyclic episodes of denudation,

which are coeval with erosion surfaces recognized elsewhere

across Africa.

The interior of southern

Africa forms part of a belt of elevated ground,

extending to East Africa, termed the “African

Superswell” (Nyblade

& Robinson, 1994), which is anomalously

high (>1000 m)

relative to average elevations of 400-500m for cratonic

areas on other continents (Lithgow-Bertelloni

& Silver, 1998; Gurnis

et al., 2000). The

latter two studies conclude, on the basis of theoretical

geophysical modelling, that the anomalous elevation

of southern Africa is related to the dynamic effects

of the extant “African Superplume”.

Their models predict that the plume-sustained topography

of southern Africa will approximate to a broad dome,

with an implied radial drainage pattern. However,

this is completely at odds with the observed first-order

topography, with the interior of the country being

the site of the relatively low-lying Kalahari sedimentary

basin, surrounded by a horseshoe arc of high ground

that is closely associated with the marginal escarpment

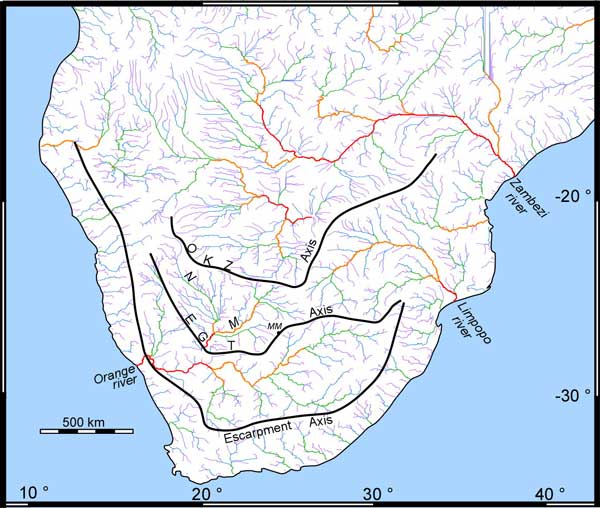

(Figure 1). Moreover, the drainage system

of southern Africa defines a remarkable pattern of

three concentric river divides, broadly parallel

to the continental margin (Figure 2), and completely

at odds with the radial drainage pattern implied

by the plume model.

Figure 1: SRTM digital elevation image

for southern Africa. The highest elevations

(purple-grey tones) are associated with the marginal

escarpment and the central Zimbabwe watershed.

This high ground surrounds the Cenozoic Kalahari sediments,

whose extent is depicted by dotted line. Elevations

in meters.

Figure 2. Drainage system of southern

Africa. Colours denote stream rank from red (1) to

purple (5). M = Molopo River, N = Nossob River, MM

= Mahura Muhtla. The major river divides are interpreted

to reflect epeirogenic uplift Axes. EGT Axis = Etosha-Griqualand-Transvaal

Axis; OKZ Axis = Ovambo-Kalahari-Zimbabwe Axes. Data

from USGS

EROS.

The three major river divides in southern

Africa cut across boundaries between Archaean cratons

and surrounding Proterozoic mobile belts, as well as

other major structural features such as the Great Dyke

(Zimbabwe), Okavango Dyke Swarm (Botswana) and late-Proterozoic

Damara belt (Namibia) (Figure 3). This argues against

a primary lithological control, and they have been

interpreted rather as axes of epeirogenic flexure (du

Toit,

1933; King, 1963; Moore,

1999). They are designated, from the coast inlands,

the Escarpment Axis, Etosha-Griqualand-Transvaal (EGT)

Axis and Ovambo-Kalahari-Zimbabwe (OKZ) Axis respectively

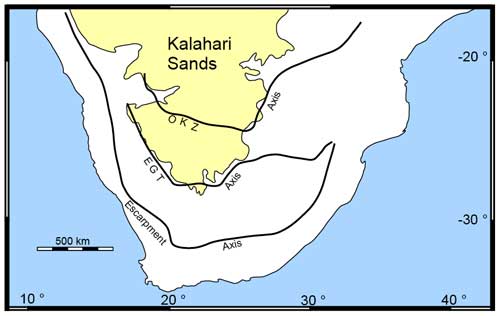

(Figure 2). The EGT and OKZ axes are closely associated

with the margins of the Kalahari basin (Figure 4),

indicating that the latter was controlled by uplift

along these two flexures (du Toit,

1933).

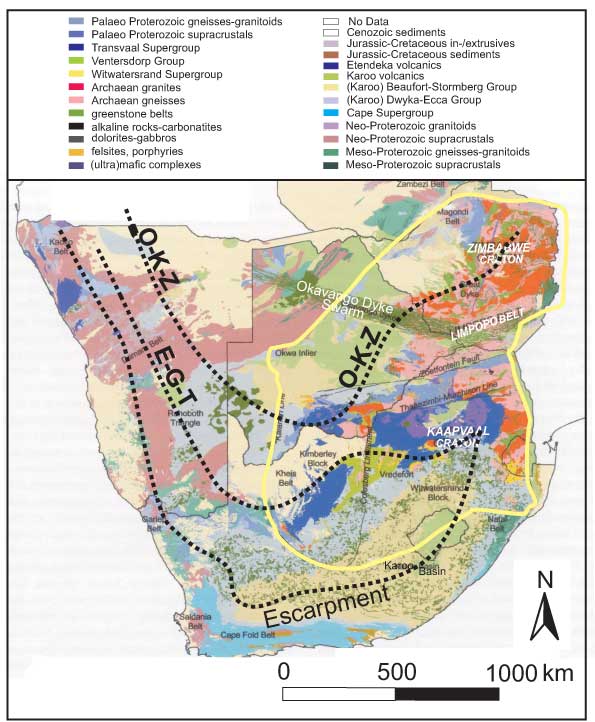

Figure 3. Loci of major river divides,

inferred to reflect axes of epeirogenic flexure, in

relation to the geology of southern Africa. These divides

all cross boundaries separating Archaean cratons from

the surrounding Proterozoic terrains. In Namibia, they

traverse the northeast-trending late Proterozoic Damara

belt at a high angle. In Zimbabwe, the O-K-Z axis transects

the granite-greenstone terrain of the Zimbabwe craton,

cuts across the NNE-trending Great Dyke, and continues

across the Okavango Dyke swarm in Botswana. The central

E-G-T axis crosses the north-trending Kheiss belt at

right angles, while much of the eastern section of

the Escarpment axis traverses readily eroded horizontal

Karoo sediments. Geology of southern Africa after De

Wit et al. (2004).

Figure 4. Distribution of the Kalahari

Formation (Kalahari Sands) in relation to the epeirogenic

axes defined by the major river divides. Note how the

EGT Axis encircles the southern margin of the Kalahari

basin. Further to the north, the eastern and western

margins of the basin are bounded by the OKZ Axis.

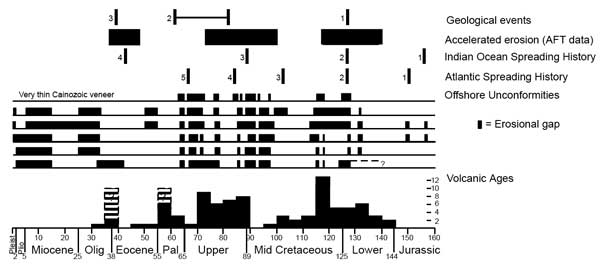

Independent geological evidence and

apatite fission track (AFT) dating, summarized in the

original paper by Moore et al. (2009), shows that the

three axes represented by the major river divides are of

different ages (Escarpment: early Cretaceous; EGT:

Upper-Cretaceous to early Palaeogene; OKZ: late Palaeogene

respectively), and thus young from the coast towards

the interior. Their ages in turn correspond closely

with major reorganizations of the spreading ridges

surrounding Africa (Figure 5). Thus, initiation of

the Early Cretaceous Escarpment Axis matches the opening

of the Atlantic and Indian at ~126 Ma (McMillan,

2003). The age of the EGT Axis corresponds closely

with major changes of the Atlantic and Indian ridge

spreading poles at ~84 and ~90 Ma respectively (Nürnberg

& Müller, 1991; Reeves

& de Wit, 2000). The late Palaeogene OKZ

axis is broadly coeval with a major spreading reorganization

in the Indian Ocean (Reeves &

de Wit, 2000) as well

as a marked increase in spreading rate at the Mid-Atlantic

Ridge (Nürnberg & Müller, 1991;

Figure 5). These temporal correlations, coupled with

the broad parallelism of the concentric river divides

and the oceanic spreading ridges surrounding southern

Africa, suggests that uplift along the continental

flexures was linked to deformation events associated

with plate reorganization. This implies long-range

transmission of stresses, through the lithosphere,

from the ridges into the continental interiors.

Figure 5. Comparison of the geological

events that constrain the ages of uplift axes, Indian

and Atlantic Ocean opening histories, offshore basin

erosion histories and ages of alkaline volcanic rocks

(based on Moore et al., 2008). Geologic events are:

1 – Start of Atlantic opening (McMillan, 2003);

2 – Maximum/minimum age bracket for disruption

of Mahura Muthla paleo-drainage (Partridge, 1998);

3 – Increased

sedimentation in the major Zambezi and Limpopo River

deltas (Walford et al., 2005; Burke & Gunnell,

2008). Offshore unconformities data are from McMillan,

(2003) within the Kwa Zulu, Algoa, Gamtoos, Pietmos,

Bredasdorp, and Orange basins respectively (from top

to bottom). Indian Spreading History from McMillan

(2003) and Reeves

& de Wit (2000): 1 – Initial rifting between

Africa and Antarctica; 2 – Commencement of spreading;

3 & 4: Changes in Indian Spreading regime recognized

by Reeves & de Wit (2000). Atlantic Spreading History

(from Nürenberg & Muller, 1991; Dingle & Scrutton,

1974): 1- Rifting extends into southern Atlantic Ocean;

2 – Commencement of opening of Atlantic (drift

sequence); 3: Estimated time of separation of Falkland

Plateau and Agulhas bank, based on assumed spreading

rates; 4 – Major shift in pole of rotation of

African/South American plates; 5 – Beginning

of progressive shift in pole of rotation of African/South

American plates. Sources of volcanic ages are quoted

in Table 1 of Moore et al. (2008). Dashed lines and

question marks are for the Chameis Bay pipes, denoting

the two different ages indicated by field relationships

and very limited radiometric dating. Click here or on image for enlargement.

The three ages of epeirogenic flexure

that initiated the major river divides are all broadly

contemporaneous with episodes of alkaline volcanism

in southern Africa. However, while the axes young from

the coast towards the interior, volcanic activity migrated

in the reverse sense, from the interior towards the

coastal margins. This inverse relationship is not readily

explained by the plume hypothesis, and we conclude

that volcanic activity was triggered by lithospheric

stresses. In concordance with the mechanisms proposed

by Oxburgh & Turcotte (1974), the broad upwarps represented

by the flexure axes would be associated with relative

tensional stresses in the upper surface of

the plate. In contrast, the lower plate

surface would experience relative tension beneath the

basins surrounding the axes.

Our observations have an important

bearing on one of the most celebrated debates in geomorphology.

This is the concept of erosion cycles, championed

by Lester King in papers published in 1949, 1955 and

1963, who recognized relics of successive erosion

surfaces of different ages in southern Africa, including

the African Surface of continent-wide distribution.

Many of the criticisms of this model focussed on the

underlying model to account for these surfaces, rather

than the evidence for their existence. Successive uplifts

along the axes represented by the major river divides

would each result in episodes of drainage rejuvenation,

thus initiating a new cycle of erosion. This provides

a series of triggers that could account for the development

of erosion surfaces of different ages. The

ages of the axes correspond also closely in age to

major unconformities recognized in the Congo basin

(Cahen & Lepersonne, 1952; Girisse,

2005; Stankiewicz & de Wit, 2006), pointing to continent-wide

episodes of erosion, as postulated by King (1963).

Acknowledgments

We thank Tyrel Flugel for producing

the Digital Elevation image of southern Africa, and

Dr. Marty McFarlane, Paul Green and two anonymous reviewers

for their constructive comments on the manuscript that

formed the basis for this web page.

References

-

Anderson, D.L. and Natland,

J.H., 2005. A brief

history of the plume hypothesis and its competitors:

concept and controversy. Geol. Soc.

Amer. Spec. Paper, 238,

119-145.

-

Anderson,

D.L. and Natland, J.H., 2006. Evidence

for mantle plumes? Nature, 450,

E15.

-

Bailey, D.K., 1993. Petrogenic

implications of the timing of alkaline, carbonatite

and kimberlite igneous activity in Africa. S.

Afr. J. Geol., 96,

67-74.

-

Belton, D.X., 2006. The low temperature

chronology of cratonic terrains. Ph.D.

Thesis, unpublished, University of Melbourne, Australia,

306 pp.

-

Bond G., (1979). Evidence

for some uplifts of large magnitude in continental

platforms. Tectonophysics, 61,

28-305.

-

Brown, R.W., Gallagher, K., Gleadow, A.J.W.

and Summerfield, M.A., 1999. Morphotectonic evolution

of the south Atlantic margins of Africa and South

America. In: Summerfield, M.A. (ed.) Geomorphology and Global

Tectonics.

John Wiley, 255-283.

-

Brown, R.W., Rust, D.J., Summerfield,

M.A., Gleadow, A.J.W. and de Wit, M.C.J., 1990. An

accelerated phase of denudation in the south-western

margin of Africa: evidence from apatite fission

track analysis and the offshore sedimentary record. Nucl.

Tracks. Rad. Measur., 17,

339-350.

-

Brown,

R.W., Summerfield, M.A. and Gleadow, A.J.W., 2002.

Denudational history along a transect across the

Drakensberg Escarpment of southern Africa derived

from apatite fission track thermochronology. J.

Geoph. Res., 107, (B12) 2350,

doi:10.1029/2001JB000745.

-

Burke, K., 1996. The African

Plate. S. Afr. J. Geol., 99,

339-409.

-

Burke, K. and Gunnell, Y. 2008.

The African Erosion Surface: a continental-scale

synthesis of geomorphology, tectonics, and environmental

change over the past 180 million years. Geol. Soc.

Amer. Mem., 201,

1-66.

-

Burke, K., Steinberger, B.,

Torsvik, T.T. and Smethurst, M.A. 2008. Plume Generation

Zones at the margins of Large Low Shear Velocity

Provinces on the core–mantle

boundary. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 286, 49-60.

-

Cahen,

L. and Lepersonne, J., 1952. Équivalence

entre le Système du Kalahari du Congo belge

et les Kalahari beds d’Afrique australe. Mém.

belge Géol., Pal., Hydrol., Soc.

Série

in -8o 4, 63 pp.

- De Wit, M.J., Richardson, S.H. and Ashwal, L.D.

(2004). Kaapvaal Craton special volume – an

introduction. South African Journal of Geology,

2004, 1-6.

-

-

Ebinger, C.J. and

Sleep, N.H., 1998. Cenozoic

magmatism throughout east Africa resulting from

impact of a single plume. Nature, 395,

788-791.

-

Fleming, A., Summerfield, M.A.,

Stone, J.O., Fifield, L.K. and Cresswell, R.G., 1999. Denudation

rates for the southern Drakensberg escarpment,

SE Africa, derived from in-situ produced

cosmogenic 36Cl: initial results. J. Geol. Soc. London,

156, 209-212.

-

Fleming, I. (1959). Goldfinger.

Cape, London, 318 pp

-

Foulger, G., 2007. The “plate” model

for the genesis of melting anomalies. Geol. Soc.

Amer. Spec. Paper 430,

1–28.

-

Gilchrist,

A.R. and Summerfield, M.A., 1991. Denudation, isostacy

and landscape evolution. Earth Surface

Processes and Landforms, 16,

555-562.

- Giresse, P., 2005. Mesozoic-Cenozoic history of

the Congo Basin. J. Afr. Earth Sci., 43,

301-315.`

-

Gurnis, M., Mitrovica, J.X.,

Ritsema, J. and van Heijst, H-J., 2000. Constraining

mantle density structure using geological evidence

of surface uplift rates: the case of the African

superplume. Geochemistry,

Geophysics, Geosystems, 1,

1-44.

-

Haddon,

I.G. (1999). Isopach Map of the Kalahari

Group, 1:2 500 000. Council for Geoscience,

South Africa.

-

Haddon, I.G. (2001). Sub-Kalahari

Geological Map, 1:2 500 000. Council

for Geoscience, South Africa.

-

Hillis, R.R., Holford,

S.P., Green, P.F., Dorž, A.G., Gatliff, R.W., Stoker,

M.S.,Thomson, K., Turner, J.P., Underhill, J.R.,

and Williams, G.A., 2008, Cenozoic exhumation of

the southern British Isles: Geology, 36, 371-374.

-

Holford,

S.P., Green, P.F., Duddy, I.R., Turner, J.P., Hillis,

R.J. and Stoker, M.S., 2009. Regional

intraplate exhumation episodes related to plate

boundary deformations. Geol.

Soc. Amer. Bull. (in

press).

-

King,

L.C., 1949. On the ages of African land-surfaces. Quarterly

Journal of the Geological Society, 104,

439-459.

-

King, L.C., 1955. Pediplanation

and isostasy: an example from South Africa. Quarterly Journal

of the Geological Society, 111,

535-539.

-

King, L.A., 1963. The South

African Scenery.

Oliver and Boyd, London, United Kingdom, 308 pp.

-

Lister,

L.A. 1987. The erosion surfaces of Zimbabwe. Bull. Zim.

Geol. Survey 90, 163 pp.

-

Lithgow-Bertelloni

and Silver, P., 1998. Dynamic topography, plate

driving forces and the African superswell. Nature,

395, 269-272.

-

McMillan, I.K., 2003. Foraminiferally

defined biostratigraphic episodes and sedimentary

patterns of the Cretaceous drift succession (Early

Barremian to Late Maastrichtian in seven basins

on the South African and southern Namibian continental

margin. S.

Afr. J. Sci., 99, 537-576.

-

-

Moore, A.E. and Blenkinsop,

T.G., 2006. Scarp retreat versus pinned drainage

divide in the formation of the Drakensberg escarpment,

southern Africa. S.

Afr. J. Geol., 109, 455-456.

-

Moore, A.E.,

Blenkinsop, T.G. and Cotterill, F.P.D., 2008. Controls

of post-Gondwana alkaline volcanism in southern

Africa. Earth

Planet. Sci. Lett., 268,

151-164.

-

Moore,

A.E., Cotterill, F.P.D., Broderick, T.G. and

Plowes, D. 2009. Landscape evolution in Zimbabwe

from the Permian to present, with implications

for kimberlite prospecting, S.

Afr. J. Geol.,

112, 65-86.

-

Moore, A.E. and Moore, J.M.,

2006. A

glacial ancestry for the Somabula diamond-bearing

alluvial deposit, central Zimbabwe. S. Afr.

J. Geol.,

109, 471-482.

-

Nyblade, A.A. and Robinson,

S.W., 1994. The African superswell. Geophys.

Res. Lett., 21,

765-768.

-

Nürnberg, D. and Müller, R.D., 1991. The

tectonic evolution of the south Atlantic from Late

Jurassic to present. Tectonophysics, 191,

27-53.

-

Oxburgh, E.R. and Turcotte,

D.L. 1974. Membrane tectonics and the East African

Rift. Earth

Planet. Sci. Lett. 22, 133-140.

-

Partridge,

T.C., 1998. Of diamonds, dinosaurs

and diastrophism: 150 million years of landscape

evolution in southern Africa. S. Afr. J. Geol., 101,

165-184.

-

Partridge, T.C and Maud, R.R.,

1987. Geomorphic evolution of southern Africa since

the Mesozoic. S.

Afr. J. Geol., 90,

165-184.

-

Reeves,

C. and de Wit, M.J., 2000. Making ends

meet in Gondwana: retracing the transforms of the

Indian Ocean and reconnecting the continental shear

zones. Terra

Nova, 12, 272-280.

-

Stankiewicz,

J. and de Wit, M.J., 2006. A proposed drainage

evolution model for Central Africa - Did the Congo

flow east? J.

Afr. Earth Sci., 44, 75-84.

-

Tinker,

J., de Wit, M. and Brown, R. 2008. Mesozoic exhumation

of the southern Cape, South Africa, quantified

using apatite fission tract thermochronology. Tectonophysics, 455, 77-93.

-

Torsvik,

T.H., Smethurst, M.A., Burke, K., and Steinberger,

B., 2006. Large igneous provinces generated from

the margins of the large low-velocity provinces

in the deep mantle. Geophys.

J. Int., 167,

1447–1460.

-

Walford, H.L., White, N.J. and

Sydow, J.C., 2005. Solid

sediment load history of the Zambezi Delta. Earth

Planet. Sci. Lett., 238,

49-63.

-

Westaway,

R., Bridgland, D., and S. Mishra, S.,

2003. Rheological differences between Archaean

and younger crust can determine rates of Quaternary

vertical motions revealed by fluvial geomorphology. Terra

Nova, 15, 287–298.

last updated 14th

April, 2010 |