Summary

The Hawaii-Emperor island

and seamount chain is the product of a long-lived

volcanic center that has moved in various directions

relative to the Pacific plate. The volcanic center

is usually referred to as a "hotspot" and

the seamount-island chain as a "hotspot track".

Age data on the Hawaii-Emperor chain indicates a remarkably

linear trend of age vs. distance from Hawaii along

the chain. Age progression continues to the oldest

seamount at the northern end of the Emperor Chain,

Meiji, 85 m.y. old. This seamount is close to the

Aleutian trench. An unanswered question is whether

the Emperor Chain once continued to the north, with

seamounts older than Meiji that have been subducted

into the trench. A corollary to this question is the

ultimate age of the hotspot – when did it initiate?

In this note I suggest that Meiji is in fact the oldest

seamount in the chain and that the hotspot initiated

as a result of significant reorganizations on the

spreading boundaries of the Pacific plate, i.e., as

a result of tectonic processes. It is probable that

other topographic features in the North Pacific such

as the Shatsky and Hess Rises were also generated

by tectonic processes. I propose that hotspots like

Hawaii are initially formed by tectonic (i.e., shallow)

processes, although the mechanisms for their longevity

remain unknown.

This posting is a summary

of a paper submitted to the proceedings of the AGU

Chapman Conference “The Great Plume Debate:

The Origin and Impact of LIPs and Hot Spots”

Tectonic

Evolution of the North Pacific

To examine initiation of the Hawaii

hotspot we need to understand the tectonic evolution

of the North Pacific. Tectonic information from the

area comes from the mapping of oceanic spreading anomalies,

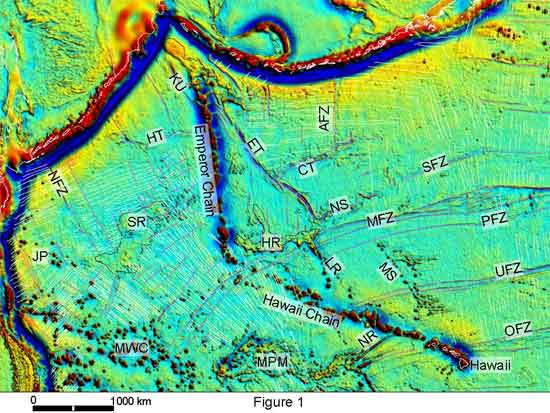

fracture zones and other topographic features (Figures

1 and 2). Topographic features (except Shatsky Rise)

show up clearly on the satellite gravity data (Sandwell,

2005) used in these figures. The most prominent

feature is the Hawaii-Emperor chain, but for now we

will concentrate on other tectonic information. Figure

1 is a view of the satellite gravity. Image processing

used to produce the figure, with artificial illumination

from the northeast, is designed to enhance subtle

features in the data; fracture zones are especially

clear. Magnetic lineations, interpreted fracture zones

and other topographic features are included in Figure

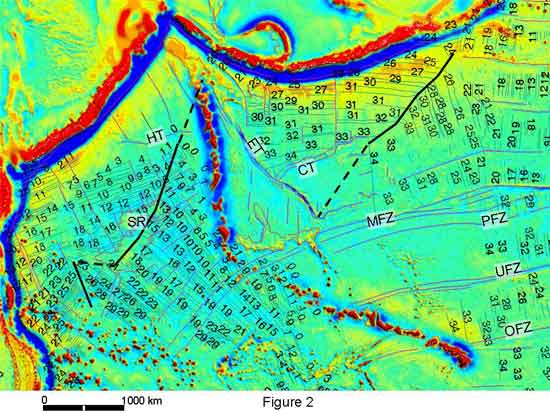

1, with named features identified. In Figure 2 the

magnetic lineations are identified, with a more subdued

gravity background. The thick black lines in Figure

2 are tracks of triple junctions where they can be

mapped from magnetic lineations; lines are dashed

where tracks are inferred within the Cretaceous normal

polarity interval.

Figure 1. Free air

gravity map of the northern Pacific (Sandwell

13.1, 2005). Thin magenta lines are mapped fracture

zones, thin yellow lines are identified magnetic lineations.

SR = Shatsky Ridge; HR = Hess Rise; ET = Emperor Trough;

CT = Chinook Trough; SFZ = Surveyor Fracture Zone;

MFZ = Mendocino Fracture Zone; PFZ = Pioneer Fracture

Zone; UFZ = Murray Fracture Zone; OFZ = Molokai Fracture

Zone; AFZ = Amlia Fracture Zone; LR = Liliuokalani

Ridge; MS = Musicians Seamounts; JP = Japanese Group

seamounts; MWC = Marcus Wake chain; MPM = Mid Pacific

Mountains; NFZ = Nosappu fracture zone; NR = Necker

Ridge; KU = Kruzenstern fracture zone; NS = Non Surveyor

feature, HT = Hokkaido Trough. Magnetic lineations

(identified in Figure 2) are from compilatioms maintained

by Larry Lawver and Lisa Gahagan at the Plates Project,

Univerity of Texas at Austin, and my own updates digitized

from Nakashini et al. (1989) and Atwater (1989). Mercator

projection; scale bar is for approximately the latitude

of Hess Rise. Click here

or on Figure for enlargement.

Figure 2. Identified

magnetic lineations in the North Pacific. Heavy black

lines track triple junctions, dashed where inferred.

M-sequence lineations are west of the Hawaii-Emperor

chain; they are numbered without the M prefix. Click

here or

on Figure for enlargement.

Previous interpretations of the

North Pacific include those of Larson & Chase

(1972), Hilde et al. (1976, 1977), Woods

& Davies (1982), Rea & Dixon

(1983), Mammerickx & Sharman (1988),

Atwater (1989) and Smith (2003).

As discussed in Norton (2006), differences

between these interpretations lie mostly in how tectonic

evolution during the Cretaceous quiet zone is interpreted.

One important difference lies in what plate(s) moved

generally northward away from the Pacific. Larson

& Chase (1972) and Hilde et al.

(1976, 1977) assume that this plate was always the

Kula plate. Woods & Davies (1982) suggested

that the Kula plate only came into existence at Chron

34 time (84 Ma) and that the plate along the northern

boundary of the Pacific plate during M-sequence time

was another plate, the Izanagi. I suggest, however,

that the earlier interpretations are correct and that

there was always only one plate bordering the northern

Pacific plate. For convenience I follow the convention

developed over the past 24 years and refer to the

Izanagi as the older plate and Kula as the younger,

but finally use the name Kula/Izanagi for the single

plate.

Tectonic evolution is presented

here as a series of figures showing progressive changes

in the Pacific, Izanagi, Kula and Farallon plate boundaries,

using the time scale of Gradstein et al.

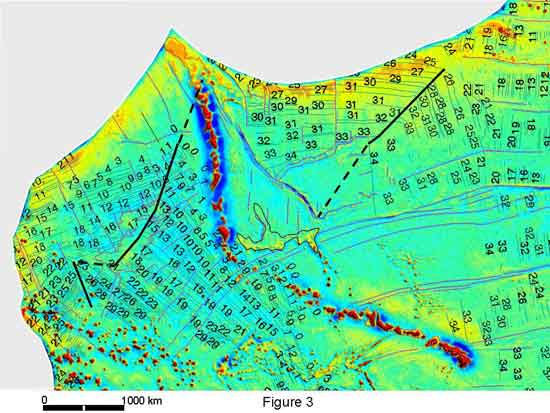

(2004). I use the gravity and tectonic data map, Figure

2, as a base. Figures step though time showing areas

of sea floor appearing as they are created. Figure

3 is a copy of Figure 2 with the area north and west

of the trench blanked out. This is done to emphasize

that the sea floor we are dealing with was a long

way from any continental margin when it formed, as

shown in Figure 4. This is a Pacific-wide reconstruction

for 80 Ma, using the plate circuit approach for calculating

relative plate positions (rotation poles from Norton,

1995). It is not possible to calculate the position

of the Pacific plate relative to the continents during

M-sequence time, as the Pacific was totally surrounded

by subduction zones and the fixed hotspot reference

frame can no longer be regarded as valid (Tarduno

et al., 2003). The plate circuit can only be

used for times later than 90 Ma, when the Pacific

became attached to New Zealand and rifted from West

Antarctica.

Figure 3. Same as

Figure 2 but with area north and west of the subduction

zone blanked out. This is done to emphasize that the

area of the Pacific that we are dealing with was tectonically

active while it was a long way from the margin. Click

here or

on Figure for enlargement.

Figure 4. Plate reconstruction

for 80 Ma. Arrows indicate relative motion across

plate boundaries (red lines) which are dashed where

inferred. Green lines are magnetic lineations, magenta

lines are fracture zones. OJP = Ontong Java plateau.

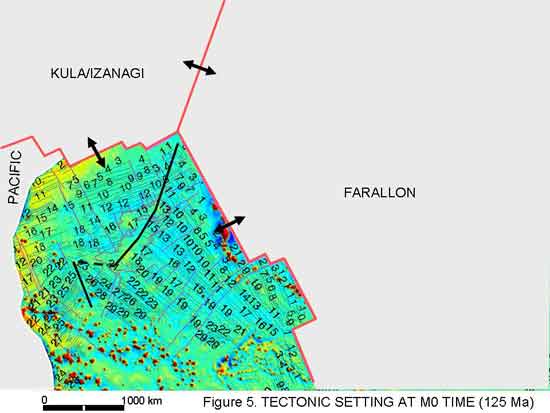

Figures 5 through 10 step through

the tectonic evolution from 125 to 71 Ma.

125

Ma (M0, Figure 5)

-

Pacific plate

boundaries are constrained by magnetic lineations.

-

Izanagi –

Farallon boundary is drawn assuming a RRR triple

junction.

-

Shatsky Rise

formed along the track of the migrating triple junction

(Sager et al., 1999).

Figure 5. Tectonic

setting at M0 time, 125 Ma. Heavy red lines are plate

boundaries, arrows show relative motion directions.

Click here

or on Figure for enlargement.

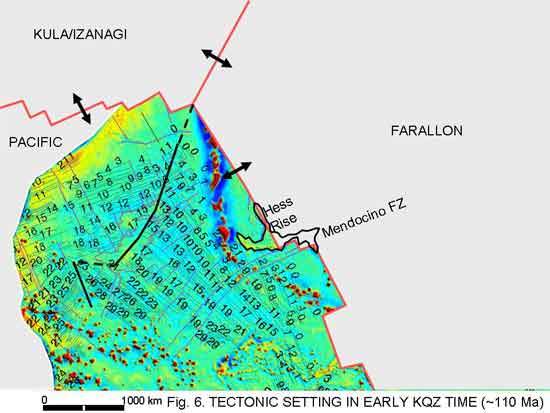

-

Pacific plate

boundaries extrapolated into the quiet zone from

the M sequence using spreading rates from Nakanishi

et al. (1989).

-

Izanagi –

Farallon boundary drawn assuming a RRR triple junction.

-

Hess Rise

straddles the presumed Pacific-Farallon spreading

axis, suggesting that the rise formed as a result

of extra volcanism at a spreading center, possibly

associated with a spreading direction change.

Figure 6. Tectonic

setting at approximately 110 Ma. Click here

or on Figure for enlargement.

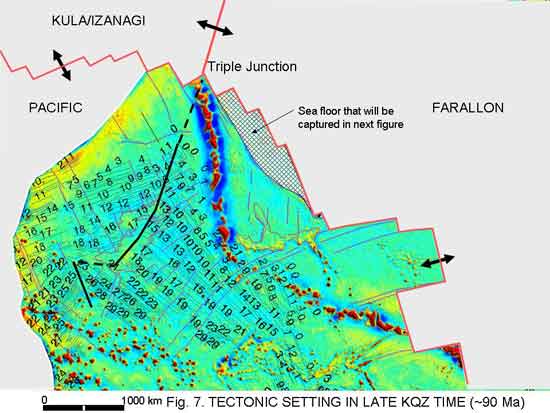

-

Pacific plate

boundaries extrapolated into the quiet zone back

in time from Chron 34.

-

Izanagi –

Farallon boundary drawn assuming a RRR triple junction.

-

Izanagi–Pacific

spreading assumed to continue in a NW direction

as implied by the Kruzenstern and parallel fracture

zones in the far north.

Figure 7. Tectonic

setting late in the quiet zone at 90 Ma. Click here

or on Figure for enlargement.

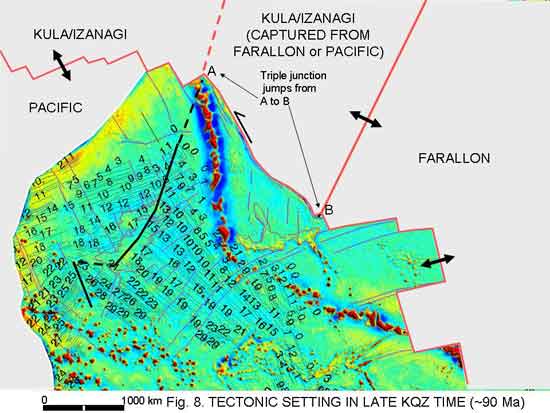

-

The time

maybe as little as 1 m.y. after Figure 7.

-

Triple junction

jumps to southeast from A to B; drawn assuming a

RRR configuration.

-

Emperor Trough

formed as a sinistral transform fault.

Figure 8. Tectonic

setting at 90 Ma after the triple junction jumped from

A to B, creating the Emperor Trough as a sinistral transform

fault. Click here

or on Figure for enlargement.

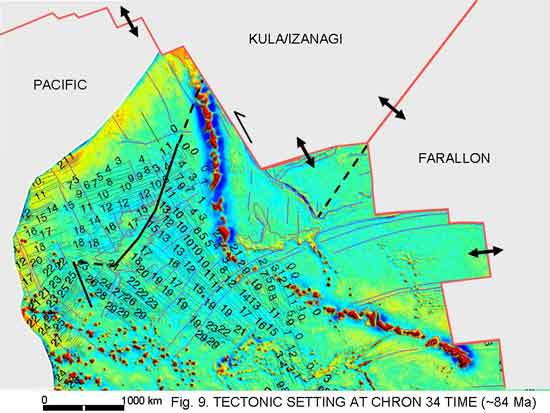

84

Ma (Chron 34, Figure 9)

Figure 9. Tectonic

setting at Chron 34, 84 Ma. Click here

or on Figure for enlargement.

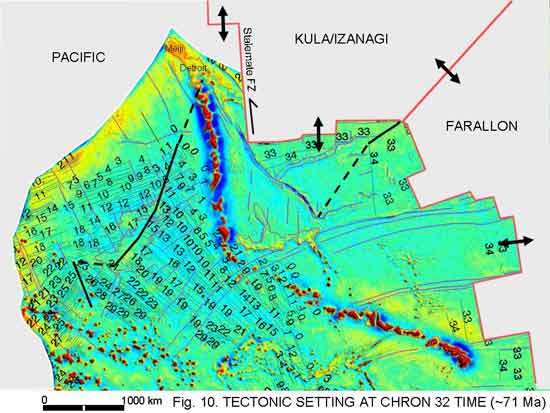

71

Ma (Chron 32, Figure 10)

Figure 10. Tectonic

setting at Chron 32, 71 Ma. Kula spreading direction

has reoriented to north relative to the Pacific plate.

Meiji seamount, which was close to the ridge axis in

the previous figure, is now several hundred kilometers

from the ridge. Click here

or on Figure for enlargement.

Implications

for the origin of the Hawaii hotspot

As presented here, Jurassic through

end Cretaceous tectonic evolution of the North Pacific

involved just three plates. These were the Pacific,

Farallon and Kula/Izanagi plates. There is no reason

to invoke extra plates such as the Chinook (Rea

& Dixon, 1983). Changes in spreading direction

implied by changes in fracture-zone- and magnetic-lineation

strike can all be accounted for with a simple three-plate

system. Anomalous topographic features in the area

were created in several ways: Shatsky Rise by excess

ridge axis-type volcanism at a triple junction (Sager

et al., 1999; Mahoney et al., 2005);

Hess Rise by excess volcanism at a ridge-transform

intersection perhaps associated with a spreading direction

change (Figure 6); Chinook Trough by ridge reorganization

also associated with a spreading direction change

(Figure 9); Emperor Trough as a fracture zone (Figure

8) and Meiji Seamount at a spreading ridge associated

with both a spreading direction change and perhaps

at the ridge left behind by a ridge jump (Figures

9 and 10).

The three-plate tectonic model

presented above, which is similar to models proposed

by Larson & Chase (1972), Hilde et

al. (1977) and Smith (2003), leads to

a scenario for initiation of the Hawaii – Emperor

seamount chain. The oldest dated seamount in the chain,

Detroit seamount (Figure 10) is 75.8 million years

old (40Ar/39Ar from whole rock

basalt samples and feldspar separates; Tarduno

et al., 2003, Doubrovine & Tarduno,

2004; Clouard

& Bonneville,

2005), although 40Ar/39Ar

ages as old as 81.2 Ma have been obtained from basalts

cored on the seamount (Keller et al., 1995).

Meiji seamount at the northern end of the chain is

not reliably dated. Based on extrapolation from Detroit

seamount, its age is thought to be about 85 Ma (Tarduno

& Cottrell, 1997; Regelous et al.,

2003). Direct evidence yields younger ages. Dalrymple

et al. (1980) reported a minumun K-Ar age of

61.9 ± 5 Ma. Fossil assemblages in overlying

sediments suggest an age of 68-70 Ma (Worsley,

1973). I assume here that these ages are indeed minimum

ages and that Meiji is as old as 85 Ma.

Geochemical evidence presented

by Keller et al. (2000), particularly strontium,

lead and neodymium ratios, are also consistent with

formation of Meiji and Detroit seamounts close to

a ridge axis. I suggest here that Meiji formed at

the Pacific – Kula/Izanagi ridge axis as a result

of excess volcanism associated with the 30° change

in spreading direction from 84 to 71 Ma shown in Figures

9 and 10. As inferred in Figure 10, Meiji may actually

have formed at an abandoned spreading center left

behind as north-directed spreading became established.

Meiji is the oldest preserved

seamount in the Hawaii-Emperor seamount chain. Whether

there were older seamounts in the chain that have

been subducted is, of course, not known. However,

if the inference from gravity data, isotopic data

and the plate boundary scenario presented above that

Meiji formed at a ridge axis is correct, it is likely

that Meiji is the oldest seamount in the chain. If

this is so, and it formed by processes related to

sea floor spreading, an important implication is that

the Hawaii hotspot also formed by processes initiated

at the (abandoned?) spreading ridge. This means that

the hotspot formed as a result of spreading processes

and plate tectonic motion. It would, of necessity,

have a shallow (upper mantle) origin. This is different

to the usual model for a hotspot as being derived

from the mantle or core remote from the influences

of plate tectonic processes and thus superimposed

on plate processes, with little interaction between

the two. The shallow model is along the lines of the

"plate model" for the Earth proposed by

Anderson

(2005) and the "alternative Earth" of

Hamilton

(2003).

Some philosophical points regarding

plate tectonic processes that are pertinent to further

discussion are:

-

Plate motion

is primarily driven by slab pull. Spreading ridges,

once established, can provide some driving force,

but they are essentially passive features that react

to spreading-direction changes by quickly re-orienting

themselves to be orthogonal to the spreading direction.

-

Volcanism

can be generated almost anywhere. There is always

a supply of magma available for eruption, provided

a suitable channel to the surface such as a rift

is created by plate forces (Favela

& Anderson,

1999). This is why almost all oceanic spreading

ridges spread symmetrically; there is no preferred

supply direction that, if it existed, would make

ridges spread asymmetrically. An impressive example

of ongoing volcanism in an extensional environment

is the Cenozoic volcanism of western North America.

See the animations by Glazner

et al.

(2005) and Walker et al. (2004); over

4,000 radiometric ages in this compilation demonstrate

how volcanism occurs all over the area, with little

evidence for geometric patterns.

-

Volcanism

has a supply and demand balance. Most spreading

ridges move along with supply (asthenospheric melt)

matching demand (the volume of material required

by spreading). As slab pull provides most of the

plate driving force, spreading rates vary widely

but for most of the world’s ridges, supply

matches demand. Hess Rise could be an example of

a case when supply briefly exceeded demand. An example

of an extensional environment where volcanism is

lacking may be the Australia-Antarctica Discordance.

In this spreading ridge system south of Australia

there seems to be a lack of volcanism (i.e.

insufficient supply) in the spreading process (West

et al., 1997).

-

There must

be flow of asthenospheric material towards ridge

axes to provide new oceanic crust. Although most

of this flow would be perpendicular to the ridge,

i.e. bringing material in from the ridge

flanks, there could be some flow along the ridge.

This scenario was elegantly investigated for several

triple junctions by Georgen & Lin (2002).

These authors showed how triple junction geometry

and spreading rates can affect axial flow in the

vicinity of the triple junction. I suggest that

at Shatsky Rise there was a net flow towards the

triple junction that resulted in excess volcanism

that created the rise.

In our supply-demand

scenario, if demand changes (spreading slows or increases),

supply simply changes as well. I hypothesize, though,

that there can be cases where supply becomes so organized

that it continues even if the spreading ridge moves

away. This could be what happened at Meiji: the spreading

ridge moved away in response to changing spreading geometries,

but volcanism was so well-established that it continued

lava generation, forming the seamount. To form the hotspot,

i.e. a long-lived oversupply situation, requires

that a melting center be formed that remains self-sustaining.

An intriguing thought is that, if a melting center can

be initially generated as a result of spreading, i.e.

shallow, processes, it could eventually tap deeper mantle

processes (the classic plume, for instance). This could

be what happened at the bend in the Hawaii-Emperor chain

– the hotspot intersected a mantle plume and changed

character. It still remains to explain, though, what

could generate a long-lived melting anomaly (hotspot)

like Hawaii, starting with tectonically-induced excess

volcanism at Meiji seamount.

Acknowledgements

I thank Gillian Foulger for

the encouragement to write this note. It arose from

conversations with Will Sager and John Tarduno at

the AGU Chapman Conference “The

Great Plume Debate: The Origin and Impact of LIPs

and Hot Spots” and their insight is appreciated.

I also thank Brian Bell, Ian Campbell, Gillian Foulger,

Warren Hamilton, Dean Presnall, Dave Sandwell and

Tony Watts for stimulating discussions. I thank Lisa

Gahagan and Larry Lawver of the Plates Project, Univ.

Texas Institute for Geophysics, for permission to

use their magnetic lineation and fracture zone compilations.

Permission from Dave Sandwell to use his gravity data

in the figures, and Doug Robertson and Bob Brovey

for their help in generating the plots, is gratefully

acknowledged.

References

-

Anderson,

D.L., 2005: Scoring hotspots: the plume and plate

paradigms, in G.R. Foulger, J.H. Natland, D.C. Presnall

and D.L. Anderson, eds., Plates, Plumes, and

Paradigms, Geol. Soc. Amer. Spec. Paper 388,

pp. 31-54.

-

Atwater, T,

1989: Plate tectonic history of the northeast Pacific

and western North America, in E.L. Winterer, D.M.

Hussong and R.W. Decker, eds., The Geology of

North America, Vol. N, The Eastern Pacific

Ocean and Hawaii, Geol. Soc. Amer., pp. 21-70.

-

Clouard,

V. and A. Bonneville, 2005: Ages of seamounts, islands

and plateaus on the Pacific plate, in G.R. Foulger,

J.H. Natland, D.C. Presnall and D.L. Anderson, eds.,

Plates, Plumes, and Paradigms, Geol. Soc.

Amer. Spec. Paper 388, 71-90.

-

Dalrymple,

G.B., M.A. Lanphere and J.H. Natland, 1980: K-Ar

minimum age for Meiji Guyot, Emperor seamount chain,

in E.D. Jackson et al., eds., Initial reports

of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, 55, pp. 677-683.

-

Doubrovine,

P.V. and J.A. Tarduno, 2004: Late Cretaceous paleolatitude

of the Hawaiian hot spot: New paleomagnetic data

from Detroit Seamount (ODP Site 883), Geochem.

Geophys. Geosys., Q11L04, doi:10.1029/2004GC000745.

-

-

Georgen, J.E.

and J. Lin, 2002: Three-dimensional passive flow

and temperature structure beneath oceanic ridge-ridge-ridge

triple junctions, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.,

204, 115-132.

-

Glazner,

A.F., 2005: Animations

of the NAVDAT database.

-

Gradstein,

F.M., J.G. Ogg and A.G. Smith, 2004: A Geologic

Time Scale 2004, Cambridge Univ. Press.

-

-

Hilde. T.W.C.,

N. Isezaki and J.M. Wageman, 1976: Mesozoic sea-floor

spreading in the North Pacific, Geophysical Monograph

19, The geophysics of the Pacific Ocean basin

and its margin, pp. 205-226.

-

Hilde, T.W.C.,

S. Uyeda and L. Kroenke, 1977: Evolution of the

western Pacific and its margin, Tectonophysics,

38, 145-165.

-

Keller, R.A.,

M.R. Fisk and W.M. White, 2000: Isotopic evidence

for Late Cretaceous plume-ridge interaction at the

Hawaiian hotspot, Nature, 405,

673-676.

-

Larson, R.L.

and C.G. Chase, 1972: Late Mesozoic evolution of

the western Pacific Ocean, Geol. Soc. Amer.

Bull., 83, 3627-3644.

-

Mahoney, J.J.,

R.A. Duncan, M.L.G. Tejada, W.W. Sager and T.J.

Bralower, 2005: Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary age

and mid-ocean-ridge-type mantle source for Shatsky

Rise, Geology, 33, 185-188.

-

Mammerickx

J. and G.F. Sharman, 1988: Tectonic evolution of

the North Pacific during the Cretaceous quiet period,

J. Geophys. Res., 93,

3009-3024.

-

Norton, I.O.,

1995: Plate motions in the Norh Pacific: the 43

Ma non-event. Tectonics, 14,

1080-1094.

-

Rea, D.K.

and J.M. Dixon, 1983: Late Cretaceous and Paleogene

tectonic evolution of the North Pacific Ocean, Earth

Planet. Sci. Lett., 65, 145-166.

- Norton, I.O., 2006: Speculations on

tectonic origin of the Hawaii hotspot, paper in preparation

for G.R. Foulger and D.M. Jurdy, eds., The Origins

of Melting Anomalies: Plumes, Plates, and Planetary

Processes, Geol. Soc. Am. Special paper.

-

Regelous,

M., A.W. Hofmann, W. Abouchami and S.J.G. Galer,

2003: Geochemistry of lavas from the Emperor Seamounts,

and the geochemical evolution of Hawaiin magmatism

from 85 to 42 Ma, J. Petrol., 44,

113-140.

-

Sager, W.W.,

K. Jinho, A. Klaus, M. Nakanishi and L.M. Khankishiyeva,

1999: Bathymetry of Shatsky Rise, northwest Pacific

Ocean; implications for ocean plateau development

at a triple junction, J. Geophys. Res.,

104, 7557-7576.

-

-

Smith, A.D.,

2003: A re-appraisal of stress field and convective

roll models for the origin and distribution of Cretaceous

to Recent intraplate volcanism in the Pacific basin,

Int. Geol. Rev., 45, 287-302.

-

Tarduno, J.A.

and R.D. Cottrell, 1997: Paleomagnetic evidence

for motion of the Hawaiian hotspot during formation

of the Emperor seamounts, Earth Planet. Sci.

Lett., 153, 171-180.

-

Tarduno, J.A.,

R.A. Duncan, D.W. Scholl, R.D. Cottrell, B. Steinberger,

T. Thordarson, B.C. Kerr, C.R. Neal, F.A. Frey,

M. Torii, C. Carvallo, 2003: The Emperor seamounts:

Southward motion of the Hawaiian hotspot plume in

Earth’s mantle, Science, 301,

1064-1069.

-

Walker, J.D.,

T.D. Bowers, A.F. Glazner, G.L. Farmer, and R. Carlson,

2004: Creation of a North American volcanic and

plutonic rock database (NAVDAT), Rocky Mountain

(56th Annual) and Cordilleran (100th Annual) Joint

Meeting (May 3–5, 2004) Paper No. 2-1

-

West, B.P.,

W.S.D. Wilcock, J.C. Sempéré and L.

Géli, 1997: Three-dimensional structure of

asthenospheric flow beneath the Southeast Indian

Ridge, J. Geophys. Res., 102,

7783-7802.

-

Woods, M.T.

and G.F. Davies, 1982: Late Cretaceous genesis of

the Kula plate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.,

58, 161-166.

-

Worsley, J.R.

1973: Calcareous nannofossils, Leg 19 of the Deep

Sea Drilling Project, Init. Reports. DSDP 19, 741-650.

|